LUCA BJØRNSTEN - LANDSCAPE

We do not immediately associate the landscape with contemporary art. The landscape painting seems to be an old art form from a bygone era. But Luca Bjørnstens latest body of work is a convincing take on what the late modern landscape painting could be. Landscape paintings which are new and different because the landscape itself has changed.

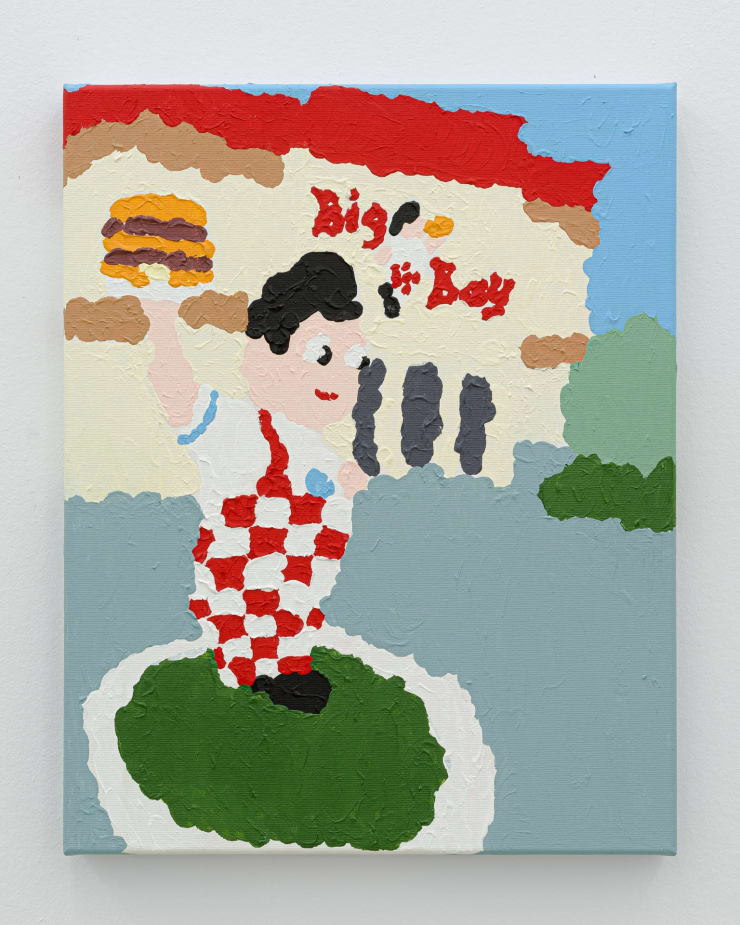

The complexity has been reduced, semiotically as well as visually; The motifs are simplified, boiled down to the minimum, just barely conserved, as if they came from a computer game of the 16-bit era with soft pixels. The landscapes of Landscape have neither depth nor width: The horizon is towering just behind the foreground and it is impenetrable and massive. And because the images are square, the landscapes feel dense and narrow. They play with and undermine our conditioned reflex to recognize a sunset as a postcard and a mountain range as the background image of a computer desktop. But while the motifs are flat – literally built from patches of solid colour – they have an almost geological structure, a landscape on the surface of the thick, lumpy layers of shiny acrylic paint in the friendly colours of Neapolitan ice cream. If romanticism and the romantic eulogy of the landscape became possible at that moment in cultural history where Man had definitely lost his intuitive and unmediated connection to nature. Then Luca Bjørnstens Landscape is possible at the historical moment, where Man has lost the unmediated connection to romanticism.

The premise of the Danish Golden Age of landscape paintings was that the link to nature was cut, so the grandness of nature could be presented as something different from Man. And once it was alienated to us, it could be idealized, idolized and mythologized. The premise of Landscape is that the link to national romanticism is being cut, so the mythologies themselves can be experienced as something radically alien to us. You feel tempted to ask yourself, is this even landscape paintings? The answer is yes, but what kind of landscapes? A landscape comes in small, medium or large. A synthetic landscape served with extra fries, where the significant coordinates are institutions like Ikea, Ferrari, Quality Street and SubWay. Equal parts irony and sincerity. The square shape of the paintings serves to mimic and substantiate this feeling of commercialized hyper-reality, in the sense that it is readily associated with the Polaroid-photography: A format popularized and proliferating as an integrated part of the Americanized consumer culture of the 60s and 70s. Landscape both recount this consumer culture and point towards its postmodern permutation, Instagram.

The diptych and triptych of the exhibition – art works consisting of two and three panels respectively – is a device historically associated with sacred art, reserved for religious themes. But here, they are prints on something as profane as cotton sweatshirts and the idyllic yet helpless Golden Age motifs, the magical swans and the red deer, could be taken directly from the 80’s Nintendo game Duck Hunt. The religious iconography merges with the watermarked and sterile universalism of Shutterstock. The gap between the motifs and the material makes us attentive to the painting, not only as reproduction, but as product.

Bjørnsten does not paint pictures of the landscapes ‘out there’, but pictures of our ‘inner’ idealized conceptions of the landscape – in a time where progress have made the earth unrecognizable and where all visual expositions have been commodified; turned into components to use in the visual identity of a brand. Today, the landscape painting is and must be something else, because the landscape has changed.

Luca Bjørnsten (born 1986, Copenhagen, Denmark) lives and works in Copenhagen. He holds a fine arts degree from Gerrit Rietveld Academie, The Netherlands. Landscape is his second solo show with the gallery.